What is an ankle sprain?

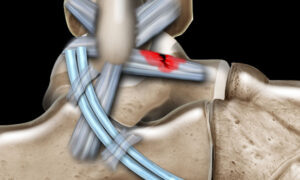

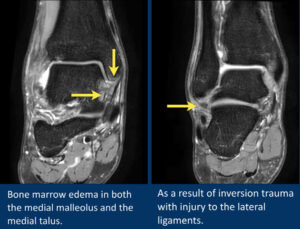

An ankle sprain happens when your foot suddenly twists and stretches the strong bands (ligaments) that support your ankle beyond their limit. This usually affects the ligaments on the outer side of the ankle, causing pain, swelling, bruising and difficulty putting weight on the foot. Ankle sprains are extremely common in everyday life and in sports like marathon running, cricket, squash, tennis and dance.

How does an ankle sprain happen in daily life?

In non‑athletes, ankle sprains often happen during simple day‑to‑day activities. Typical examples include missing a step on the staircase, slipping off the edge of a pavement, walking on uneven ground or stepping into a small pothole or gap. The foot rolls inwards, the ankle rolls outwards, and the ligaments on the outside of the ankle get overstretched or torn.

Sport‑specific mechanisms of injury

In sport, the same basic twist happens, but often at higher speed and force:

-

Marathon runners: Fatigue, uneven roads, potholes and sudden changes in direction at aid stations can cause the foot to roll inwards during landing or push‑off, especially when the runner is tired late in the race.

-

Cricketers: Bowlers and fielders are at risk when sprinting, cutting, turning quickly to chase the ball, or landing awkwardly from a jump or dive; landing on an uneven patch or another player’s foot is a common trigger.

-

Squash, tennis and other racquet sports: Fast side‑steps, sudden stops, split‑steps and landing on an opponent’s or partner’s foot can all cause the ankle to roll sharply inwards. Video studies in court sports show many sprains happen when landing from a jump or changing direction with the foot fixed to the floor.

-

Dancers: Repeated jumps, turns and work on demi‑pointe/pointe put the ankle at risk when landing poorly, losing balance in turnout or rolling over the foot at the end of a jump

Dancers: Repeated jumps, turns and work on demi‑pointe/pointe put the ankle at risk when landing poorly, losing balance in turnout or rolling over the foot at the end of a jumpIn all of these, the common pattern is a sudden inward twist of the foot with the body weight moving over it too fast for the muscles to protect the ligaments.

What is a chronic ankle sprain?

Sometimes the ankle never fully recovers from the first sprain, or it keeps getting sprained again and again. This is often called a “chronic ankle sprain” or “chronic ankle instability.” It means the ligaments and supporting muscles are no longer giving the joint the firm support and balance it needs, especially during quick or unpredictable movements.

Typical symptoms of chronic ankle problems include:

-

Repeated “giving way” or rolling of the ankle on uneven ground or during sport

-

A constant feeling of weakness or wobbliness in the ankle

-

Swelling or ache after walking, running, training or dancing

-

Stiffness or tightness, especially in the morning or after sitting

-

Fear or lack of confidence while running, jumping or changing direction

Chronic ankle issues do not usually improve with rest alone. Without proper sports physiotherapy and ankle sprain rehab exercises, they can lead to more sprains, early joint wear‑and‑tear and ongoing pain.

-

Key sports physiotherapy principles :-

After an ankle sprain, the goal is not to just “rest it” but to protect it briefly, control the swelling, and then start gentle, pain‑free movement as soon as it is safe. This early movement and gradual loading help the ligaments heal stronger and reduce stiffness.

As the pain settles, the focus shifts to building strength, balance and coordination around the ankle, often using a brace or taping for extra support while you move and train. These exercises train the muscles and nerves to react quickly again, which lowers the chance of the ankle rolling over in the future.

Instead of clearing you to play simply after a set number of days, your rehab should follow clear stages, from light everyday activity to full training and competition. At each stage your physiotherapist checks whether your strength, balance, hopping and sport‑specific skills match the other leg, and only then moves you to the next level or back to sport

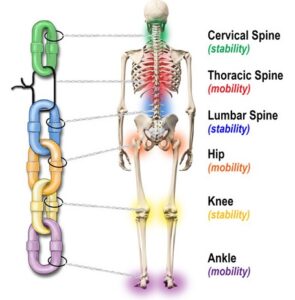

Sports‑specific biomechanics and pathomechanics

- Marathon runners: Repetitive loading at mid‑stance and push‑off demands optimal dorsiflexion, elastic calf function and dynamic peroneal stability; limited dorsiflexion and poor neuromuscular control increase re‑injury risk, even when gross running gait looks “normal.”frontiersin+1

- Cricketers: Bowlers and fielders experience high inversion moments during cutting, landing and boundary stops; lateral instability alters kinetic chain alignment, affecting knee, hip and lumbar mechanics during bowling and throwing.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+1

- Squash/tennis/racquet sports: Multi‑directional lunges, split‑steps and rapid deceleration place high demand on frontal‑plane control; impaired proprioception and peroneal latency compromise change‑of‑direction mechanics and increase risk in side‑stepping and cross‑over steps.sciencedirect+1

- Dancers: Repeated demi‑pointe, jumps and landings require end‑range plantarflexion control; lateral ligament injury disrupts alignment in turnout, landing mechanics and pointe control, increasing risk of chronic instability.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih+1

Acute vs chronic ankle sprain

-

Acute ankle sprain

This is a “fresh” injury that has just happened, usually within the last few days or weeks.

The main features are sudden pain, swelling, bruising and difficulty walking after you twist or roll your ankle. The focus here is ruling out a fracture, calming pain and swelling, and then starting early, guided rehab so it heals well. -

Chronic ankle sprain / chronic ankle instability

This refers to ankle problems that keep going for months, or repeated sprains over time.

People often describe the ankle as weak, wobbly or “giving way,” especially on uneven ground or during sport. There may be on‑and‑off swelling or aching after activity, and confidence in the ankle is usually low. Chronic cases need a full strengthening and balance programme, sometimes extra bracing, and occasionally surgical opinion if rehab alone is not enough.

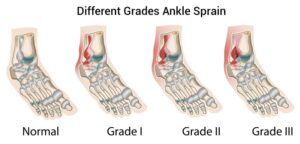

Grading of acute ankle sprains (Grade I–III)

Most research and clinical guidelines still use a three‑grade system to describe how badly the ligaments are hurt:

-

Grade I (mild)

The ligaments are stretched but not torn.

There is mild pain and swelling, but you can usually walk with only slight discomfort. Recovery is often quick with proper care. -

Grade II (moderate)

Some of the ligament fibres are torn.

Pain, swelling and bruising are more obvious, walking is painful and the ankle may feel a bit unstable. Rehab takes longer and needs structured physiotherapy to fully restore strength and balance. -

Grade III (severe)

The ligament is completely torn, and sometimes more than one ligament is involved.

There is significant pain, swelling and bruising, weight‑bearing is very difficult, and the ankle feels very unstable. Recovery is longer, and in some cases a specialist may discuss more intensive treatment or, rarely, surgery, along with a long, detailed rehab plan.

Management of ankle sprains:-

“Treatment is planned according to how new the sprain is and how badly the ligament is damaged, rather than using a ‘one size fits all’ approach.”

| Type / Grade | What it means (simple) | Main goals of treatment | Typical support & activity level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute – Grade I (mild) | Ligament is stretched but not torn; mild pain and swelling; you can usually walk with some discomfort. | Calm pain and swelling quickly, protect the ankle briefly, then start gentle movement and gradual loading so it does not get stiff or weak. | Short period of protection (brace/taping), home care for swelling, early comfortable movement, then gradual return to walking, daily tasks and light sport. |

| Acute – Grade II (moderate) | Some fibres of the ligament are torn; more pain, swelling and bruising; walking is painful and ankle may feel a bit unstable. | Protect the joint while it settles, then carefully restore full movement, strength and balance so the ankle feels stable again. | Stronger external support (brace/taping, sometimes crutches for a few days), clinic‑based rehab, step‑by‑step return from daily activities to jogging and then sport, usually over several weeks. |

| Acute – Grade III (severe) | Ligament is completely torn (often more than one); marked swelling and bruising; very hard to put weight on the foot. | Give the ligament time to heal in a protected position, then follow a long, structured rehabilitation plan to regain movement, strength, balance and confidence. | Firm support (boot or rigid brace) and reduced weight‑bearing at first, followed by closely supervised rehab; gradual return to normal walking, then sports; sometimes a specialist opinion if the ankle stays very unstable. |

| Chronic ankle sprain / chronic instability | Ankle feels weak or “keeps rolling” months after the first injury, or there are repeated sprains. | Improve long‑term stability, reduce “giving way,” and prevent further sprains by training the muscles, balance and control around the ankle. | Detailed assessment, longer rehab programme focusing on stability and control, possible regular use of brace/taping for higher‑risk activities, and ongoing “maintenance” exercises to keep the ankle strong. |

Sport‑specific rehab and return‑to‑play

| Sport | Rehabilitation Focus | Return-to-Play Principles |

|---|---|---|

| Marathon Runners | Early gradual return to running, progressive walking to jogging, strength building for calf muscles, improved balance and coordination to support running mechanics even if gait looks normal | Gradual increase in running load and pace, ensuring pain‑free movement and stability in running pattern before full return |

| Cricketers | Phased running drills starting with straight-line running progressing to curves, cutting, sliding, and landing; strengthening of trunk and hips to support complex movements like bowling and fielding | Systematic progression through cricket-specific movement patterns, working towards full bowling and fielding actions under supervision |

| Racquet Sports (Squash, Tennis, etc.) | Focus on single-leg strength, lateral balance and agility, multi-directional movement drills including split steps and lunges tailored to court demands | Increasing intensity of court-specific drills and match-like movements only after achieving adequate strength, balance, and control |

| Dancers | Gradual progression from controlled barre work to centre stage, enhancing single-leg endurance, landing control, and supporting complex turns and jumps | Slowly advancing to full choreography and performance, often with external support (like taping) during early return phase to reduce risk of recurrence |

| All Sports | Supervised physiotherapy focusing on neuromuscular training and proprioception (body awareness), with clear, objective criteria to measure progress before returning to sport | Phased rehabilitation models emphasizing return to activity, sport, play, and competition steps using strength, balance, hop, and sport-specific functional tests |

References:-

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC164373/

- https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/mgh/pdf/orthopaedics/sports-medicine/physical-therapy/rehabilitation-protocol-for-ankle-sprain.pdf

- https://www.sanfordhealth.org/-/media/org/files/medical-professionals/resources-and-education/014000-01095-flyer-ankle-sprain-rehabilitation-pt-guideline.pdf

- https://patialaheart.com/blog/ankle-sprains-diagnosis-treatment-and-rehabilitation-for-athletes/

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Ankle_Sprain

- https://ijspt.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/8-Flore.pdf

- https://www.massgeneral.org/assets/mgh/pdf/orthopaedics/foot-ankle/pt-guidelines-for-ankle-sprain.pdf

- https://www.narayanahealth.org/blog/rehabilitation-for-ankle-sprains-everything-you-need-to-know

- https://www.orthobullets.com/foot-and-ankle/7028/ankle-sprain

- https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/recovery/foot-and-ankle-conditioning-program/

- https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2001/0101/p93.html

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1907229-treatment

- https://www.orthobullets.com/foot-and-ankle/7028/ankle-sprain

- https://www.nata.org/sites/default/files/2025-08/ankle-sprains.pdf

- https://www.europeanreview.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/1876-1884.pdf

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.868474/full